9. Learning

The purpose of learning is growth, and our minds, unlike our bodies, can continue growing as we continue to live.

Mortimer Adler (20c philosopher)

Learning is so important that we are all born with a love for learning. You don’t need to nudge babies to learn, they just love it! However, this urge may be distorted in time, like our eating habits – we don’t always learn what is good for us, but learn junk instead. So let’s see how we can keep the flame of love for learning alight. Some tips for improving your memory will be suggested too, but let’s start with considering various learning styles.

Learning styles

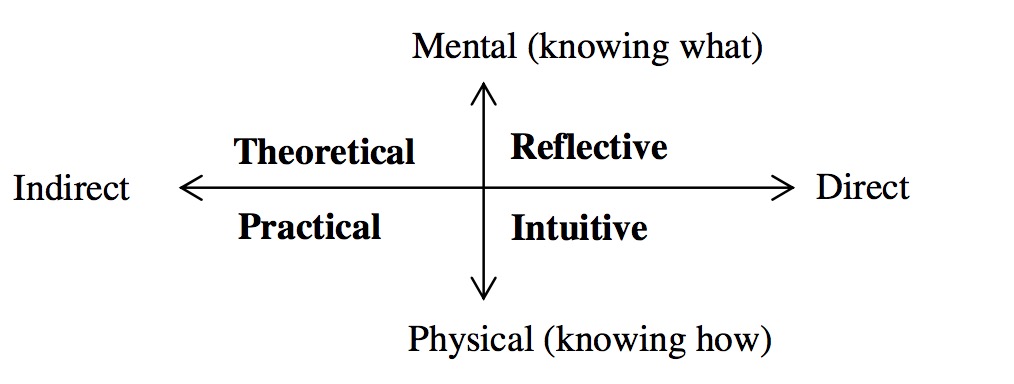

There are four learning styles:

Theoretical learning is indirect mental learning. Indirect means that you learn from books and others. What distinguishes this mode from simple memorising is understanding. Understanding requires active engagement (questioning, clarifying, etc.), an enquiring mind and interest in the subject. This is easier if you relate the new to what you already know (make connections!).

Intuitive learning is direct physical learning – you learn by experience. Learning how to ride a bike is an example. Of course, others can help you and encourage you while you are doing so, but you have to figure out yourself how to keep your balance. This is why intuitive learning often involves trial and error (you may fall down a few times before you get the knack).

Practical learning is indirect, physical learning. You learn to do something from others or manuals (e.g. learning to drive). It is most useful when knowledge gained this way becomes mainly unconscious and instinctive. This is achieved through practising.

Reflective learning is direct mental learning based on your own thinking and personal experience. It can have an important role in forming opinions, judgements, assessments and views.

In reality, several types of knowledge (associated with the above learning styles) are often combined. For example, doctors combine practical and theoretical knowledge; in social occasions you may need all four: theoretical (to be informative), intuitive (to be spontaneous) practical (to be polite), and reflective (to be interesting). None of these styles is superior. In fact, it can sometimes be dangerous not to combine them (e.g. learning how to use a gun may be unsafe if you don’t know how to control your impulses or do not reflect on possible consequences). Which learning style do you like most and which one least? Considering that they all matter, what can you do to like the latter a bit more?

This exercise aims to connect you with the innate drive to learn. Use it whenever your motivation to learn is low.

Uplifting learning: recall situations when you have enjoyed learning. It could be a skill such as swimming or playing a game; a new school subject; something interesting from the internet or a book; insights that you have gained from thinking about or discussing certain issues. Try to recapture as best as you can the sensation you had then. Remember how it feels. This can come in handy when your motivation to learn is low, especially if it belongs to the same learning style (e.g. if you want to motivate yourself to learn about psychology, recall a situation in which you were curious about something, read about it, and enjoyed understanding it better).

Learning tips

- If you are interested, learning is easy – so the top tip is to get curious and interested in the subject.

- Understand or master the basics. This allows you to build on the solid foundations. So, first lessons are the most important.

- Make gradual, incremental steps without big leaps and try to connect the new to what you already know.

- Make a link between what you are learning and your own experience (e.g. link physics to skateboarding, sailing or golf).

- Imagine what you are learning (Einstein created the theory of relativity from imagining that he was riding a beam of light).

- Summarise a long text to a few sentences or bullet points.

- Draw a diagram or a picture of what you want to remember.

- Try to explain or imagine that you are explaining what you have learnt to somebody else (this also increases motivation).

Retention

These suggestions can help us remember what we learn.

- Forget what you don’t need to remember. If we cram our heads with unimportant information it should not come as a surprise that we can’t remember what really matters!

- Retention is better if information is related to personal experience and if it is meaningful. The latter involves either understanding an already implied meaning or deliberately connecting various elements in a meaningful way (see below).

- Feelings and sensations have the deepest impact on memory, then images, and finally abstractions and symbols (e.g. words). So, abstract information is easier to remember if it is connected to a feeling, sensation or image. For example, a particular scent may assist your memory if it is present during learning and at the time of recalling (e.g. an exam). Using the same sensation in unrelated situations will decrease its effectiveness though.

- Research also indicates that retention is easier if the context at recall matches the context at learning (e.g. if you recall information in the same room in which you learned it)(1).

Mnemonic techniques

Mnemonic techniques are usually used to remember names, a list of items or numbers. They can be grouped in two categories: one based on visualisation and the other on meaning making:

Visualisation

- Associate a name you want to remember with an image of a similar word. So if you want to remember the capital of Australia (Canberra) imagine a slice of Camembert cheese sitting on top of the map of Australia; if you are introduced to somebody called Rosie, imagine her wearing a hat with roses.

- Imagine your house or flat. Place each item you want to remember in different parts of your house (e.g. the hall, staircase, bathroom, sitting room etc.). Then, imagine walking through it when you try to remember them.

- Associate each number to be remembered with an image (e.g. 1 = street lamp, 2 = swan, 3 = flying bird, etc.) and then create a picture or clip from these images (e.g. 231 = a swan makes a bird fly off and hit a street lamp).

Meaning

- Create a story that includes all the items to remember.

- To memorise the spelling of a word, for example, create a sentence out of words that start with letters that make up that word (e.g. because – Big Elephants Can Always Upset Small Elephants).

- Make a meaningful sentence out of the items you want to remember or their first letters. For example, the order of the first three colours in snooker (the most difficult to remember): God Bless You – Green, Brown, Yellow

The order of operations for maths is: Parentheses Exponents Multiply Divide Add Subtract – Please Excuse My Dear Aunt Sally

(1) See, for example, Matlin, M. (1983) Cognition. London: Holt, p.85.