10. Reasoning

10. Reasoning

To treat your facts with imagination is one thing, but to imagine your facts is another.

John Burroughs (19c naturalist)

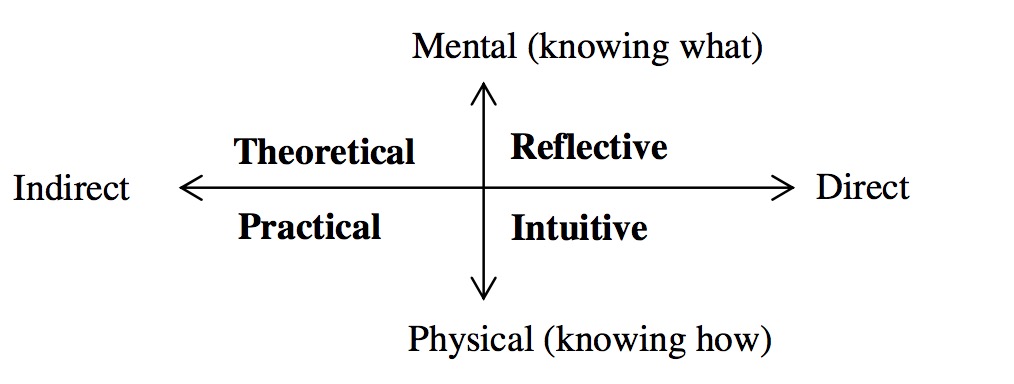

Reasoning is an ability to make assessments and judgements, draw conclusions, and form views and ideas. This capacity depends on our ability to hold several pieces of information in awareness and connect them in a way that is helpful to deal with an issue or situation. Our own inertia and preferences conspire against it though, so we will start by addressing lazy and biased thinking first, and then we will turn to objectivity and realistic thinking.

Lazy thinking

Reasoning can be seen as agility or fitness of the mind, which means that it can be strengthened through practice: the more you exercise your reasoning the better you will be at it. Moreover, as physical exercise makes our bodies firmer and nicer, exercising our reasoning capacity makes our thoughts nicer and more elegant. If we don’t do so, the opposite happens – we backslide into lazy thinking. These are some examples of lazy (sloppy) thinking:

- Over-generalising: making general judgements on the basis of limited experience or a few instances of a situation (e.g. misusing never, always, or all as in ‘He never does the dishes, it is always me!’, ‘All politicians are crooks’).

- Impulsiveness: jumping to conclusions without checking (e.g. ‘mind reading’ or ‘fortune telling’: assuming that you know what somebody is thinking or what she will say or do).

- Selective exposure: exposing ourselves only to information which we know beforehand is likely to support what we already believe (e.g. a right-wing person who reads only right- wing newspapers or relies only on right-wing websites).

- Rigidity: unwillingness to consider alternatives to an initial judgement or conclusion.

- Over-simplifying: as in the case of black-and-white thinking (e.g. vilifying one side of a conflict and glorifying the other).