7. Excitement

7. Excitement

Most of the evils of life arise from man’s being unable to sit still in a room.

Blaise Pascal (17c French philosopher)

Excitement refers to the intensity of affective experience and can be associated with both positive and negative emotions. It is linked to the activation of the sympathetic nervous system and measurable physiological effects (increased heartbeat, pulse, perspiration and adrenalin level). Excitement influences our thinking, decisions, behaviour and emotional reactions. In many cases it is not emotions that cause trouble, but their intensity. This is why being able to manage excitement may come in handy.

The effects of excitement

Excitement is a surge of additional energy developed primarily to enable an organism to act more promptly. However:

- Excitement can be experienced even if an action is not needed or before it is needed. This usually happens when we expect or imagine something, and it may lead to a slippery slope if excitement and these images create a vicious circle.

- Intense excitement can diminish attention and concentration as well as lead to distorted perception and judgements.

- It can also amplify emotional responses (so joy becomes euphoria, fear becomes panic, anger becomes rage).

- Excitement affects self-control, can cause unpredictable reactions and increase susceptibility to influence.

- A persistently high level of excitement may even affect physical and mental health.

- Moderate excitement is desirable though, often sought to counter boredom. What would life be without getting excited? However, if excitement becomes a need or an end in itself, it can be addictive and lead to prioritising intensity over quality – which, in fact, increases boredom in the long run.

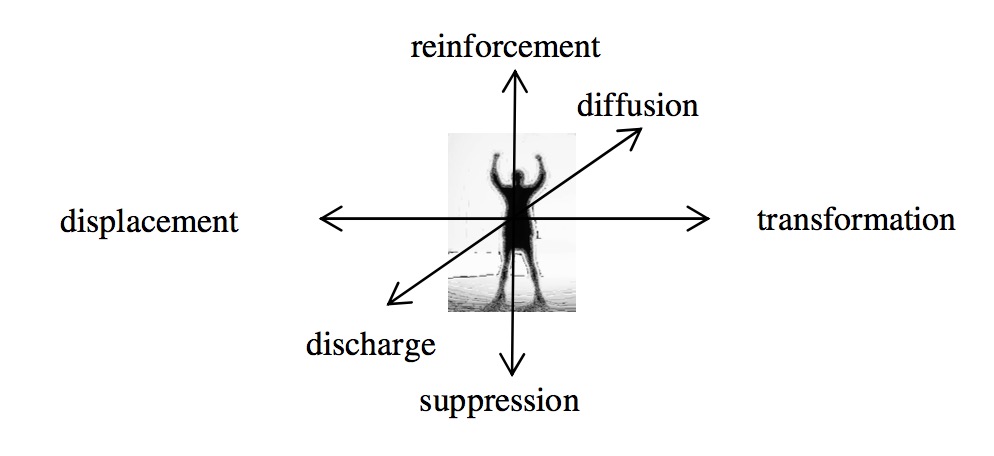

Evidently, excitement plays a complex role in our lives, so let’s see what we can do about it.